What young people have to say about race and inequality in South Africa

Kira Erwin, Durban University of Technology and Kathryn Pillay, University of KwaZulu-Natal

Meritocracy is the belief that holding power or success should be judged on people’s individual ability, rather than on wealth or social connections. At first glance, this appears to be a reasonable proposition. But the focus on individual merit becomes harder to fathom as one enters the messy world of structural inequality and discrimination.

As our research shows, ideologies of meritocracy and individualism create obstacles for collective action towards a more equal and just society. Our findings were published in the book Race in Education, the outcome of a thinktank on the effects of race at the Stellenbosch Institute for Advanced Study.

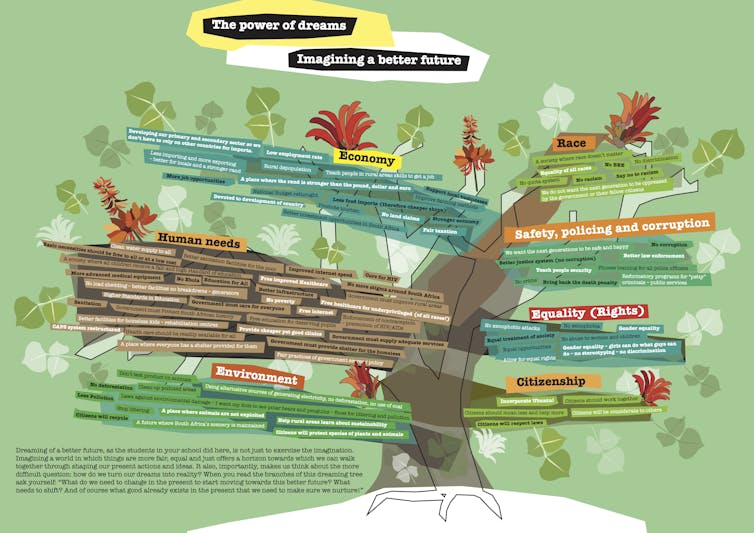

Using a methodology called Dreaming Workshops, our study explored how Grade 11 students, of around 16 and 17 years old, from different schools in the South African coastal city of Durban imagined race, racism and non-racialism in a utopian future.

Young South Africans are being socialised into a highly racialised society and experience severe disparities. Expecting them to eradicate racism without dismantling material inequalities is a deferral of adult responsibility. Mindful of this, we designed a study to listen to young people’s ideas, as opposed to looking to them for solutions.

Complex views

The five schools that participated in this study, three government and two private, are located in a middle-class, formerly “white” area in Durban. The schools have, on average, a diverse but mostly middle-class student body, with some students travelling from townships to attend class. Under apartheid townships were poorly resourced and under-serviced residential spaces designated for people racialised as black. Each school in the study had approximately 20 students per class. One school markets itself as girls-only, one as boys-only, the other three are open to all genders.

Young people involved in the study were deeply aware of inequality. For them, reducing inequality was a priority if the country was to move towards a better future.

It is notable that non-racialism was not a concept volunteered by any of the students as a future ideal, despite it being a constitutional principle in South Africa. At present there is little clarity on the meaning of non-racialism. It is equated to a multiplicity of ideas, among them mobilisation against apartheid, multiracialism, multiculturalism, nation-building, and race-blindness.

Supplied

What students did want eradicated from their utopia was racial discrimination and racism. The meanings they attached to race shifted depending on the conversation, for example, race when it related to racial quotas as opposed to race when it related to culture, identity or politics.

Racial identities played an important role in these young people’s sense of self. But some thought it is the “weirdest thing ever” that people sit in “race groups” during lunch breaks. They make sense of this by explaining that people sit with others who share their culture. Using race and culture as proxies for each other is very much part of the South African experience of racialisation.

The “commitment” to racial identities, however, was more complex than it first appeared. There was an uneasiness between accepting and feeling pride in racial identities, and not wanting them to count as measures of social value. They frequently vocalised a rejection of racial stereotypes and racism.

Tensions

In each school, there were students committed to eradicating their own racist thoughts, who openly challenge parents and family members about racism and actively refused to essentialise their peers. Students felt a generational responsibility to challenge racial stereotypes.

They were also vehemently against race as a category in government policies. Arguments against racial quotas, such as broad-based black economic empowerment and affirmative action (race-based legislation aimed to redress past and current discriminations) were present in all the schools. As were statements that “we need to get over blaming the past”, or linking poverty with laziness, or refusing to recognise the role of privilege in individual achievement.

These sentiments reflected a socialisation process happening at schools, and in the family, that raised real tensions for young people. Many students were taught to believe that individual hard work pays dividends. Principles of individual success and meritocracy were well established in their homes, and valorised daily at their schools. Schools acutely focused on individual competition in sports and academic achievements, rewarding individual rather than collective effort.

The “wiping out” of the individual in favour of a group racial identity for employment and university entry appeared unfair and contradictory to the meritocratic values they were being taught to aspire to.

Read more:

We need to unpack the word ‘race’ and find new language

These views were present in students who would be racialised as belonging to all four of South Africa’s racial categories, socially constructed in this country as black, Indian, Coloured and white.

Meritocratic arguments were also against the redistribution of wealth in South Africa. Taxing the rich was often seen as “making the poor lazy”. Here, class privilege was indiscernible from what would usually be thought of as a defence of white privilege.

Dilemma

In our view meritocratic sentiments are highly problematic in the context of structural inequality. In South Africa there is no equal playing field on which to justify individual merit.

It is not just race-blindness that we should guard against in South Africa; class-blindness too leads to a repetition of the status quo. Since structural inequalities fundamentally enable reproductions of racism this creates a complex dilemma for these students.

What does it mean to desire social justice and equality but refuse to “give up” any privileges?

This dilemma poses a challenge for education in South Africa. Certainly more frank and critical classroom conversations on race, class and culture are needed. More pressing is how to restructure schooling so that it is less focused on individual merit and reward.

This article is part of a series. Other authors include Barney Pityana, Göran Therborn, Nina Jablonski, George Chaplin and Njabulo Ndebele.

The three edited volumes of essays published by African Sun Media in 2018 (The Effects of Race, edited by Nina G. Jablonski and Gerhard Maré), 2019 (Race in Education, edited by Gerhard Maré), and 2020 (Persistence of Race, edited by Nina G. Jablonski) contain the complete representation of the project’s scholarship.![]()

Kira Erwin, Senior researcher, Durban University of Technology and Kathryn Pillay, , University of KwaZulu-Natal

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Written by: Zuko

What young people have to say about race and inequality in South Africa

Similar posts

MORE ARTICLES

Two boys accused of killing Grade 10 pupil remain behind bars

45 individuals arrested in Pretoria for drunk driving over the weekend

Pics: Inside Liesl Laurie-Mthombeni’s girls’ vacation

Berita celebrates 34th birthday with new single ‘Gugulethu’

Gauteng settles major e-toll debt with R5.4 billion payment

QUICK LINKS

UpComing Shows

959 Music Weekdays

Kaya 959 Hits

Real. Familiar. Memorable. Kaya 959 brings you the music you know and love from our playlist. Uninterrupted. Thursdays 20h00 to 21h00

close

The Best T in the City

With T Bose

He has held it down in the world of mid-morning radio with the best music, riveting topics, brilliant mixes and interesting guests. Every weekday, The Best T proves why he is the BEST by connecting to you like only your bro or favourite uncle could. He lets his listeners dictate the songs they want to hear in the ever-popular Top 10 at 10, and his Three Teaspoons never run out. Catch The Best T in the City Mondays to Fridays from 09h00 to 12h00.

close

Feel Good

With Andy Maqondwana

Feel good about feeling good! That's exactly what The Feel-Good show is about. An escape from the negativity that surrounds us, indulging you in good feels. Pass it on to one and all. Spread the good feeling around Gauteng with Andy Maqondwana.

close

Kaya Biz

With Gugulethu Mfuphi

The world of business is simplified for you by Kaya Biz with Gugulethu Mfuphi. This fast-paced award-winning business show talks to the corporate giants as well as up and coming entrepreneurs about their wins and challenges. Gugulethu invites guests to offer their analyses of markets and economies, and also delves into issues of personal financial wellness. Kaya Biz airs Mondays to Thursdays 18h00 to 19h00.

close

Point of View

With Phemelo Motene

Point of View with Phemelo Motene delves into the day’s current affairs, touches on real issues that affect people’s daily lives and shares expert advice on questions posed by the audience. Mondays to Thursdays 20:00 to 22:00.

closeConnect with Kaya 959

DownLoad Our Mobile App

© 2025 Kaya 959 | On The Street On The Air