Student resistance in South Africa: the SASO nine trial and Steve Biko

By: Anne Heffernan, Durham University

South African History Online

Anne Heffernan, Durham University

Student protests swept across South African campuses in 2015 and 2016 under the banner of #FeesMustFall. The protests revitalised public interest in student politics.

My recently published book, Limpopo’s Legacy offers a historical perspective on these events. In it I analyse regional influences that have underpinned South African student politics from the 1960s to the present.

Student organisations in the Northern Transvaal (today Limpopo Province) have influenced political change in South Africa on a national scale, and over generations. At the centre was the University of the North at Turfloop (now called the University of Limpopo). The institution played an integral role in building the South African Students’ Organisation (SASO) in the late 1960s and propagating Black Consciousness in the 1970s.

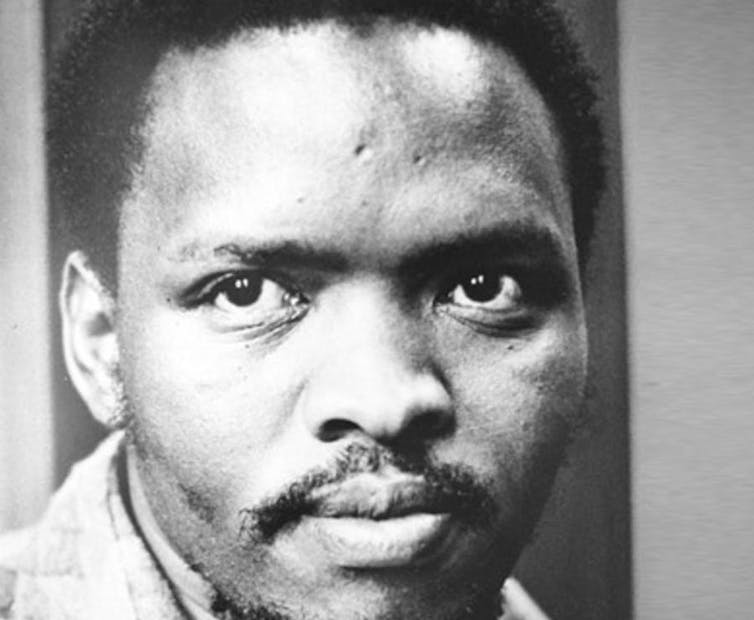

There are lessons from half a century ago for South Africa’s most recent student uprisings. Profound insights can be drawn from the trial of nine SASO activists, in particular what was said in the witness stand by one of the founders of SASO, Steve Biko.

SASO and black consciousness

SASO was an organisation launched by university students on the segregated campuses of so-called ‘non-white’ universities. It created an organisational space for black students. It argued that other student organisations, such as the multi-racial National Union of South African Students, were dominated by white interests.

SASO students developed the philosophy of Black Consciousness, arguing that psychological liberation was necessary for political liberation. They offered a new way for black South Africans to think about themselves and their place in their country.

In this SASO offered a new approach to liberation, led by a new generation, that differed from older groups like the African National Congress and the Pan African Congress.

In ways that still resonate with student activists today, SASO criticised these older organisations for being quiescent and failing to achieve the promise of liberation.

The state’s response

The apartheid state initially saw SASO as racially separatist, and allowed it to organise on campuses in the early 1970s. But by the middle of that decade the state began to crack down on these student activists.

In July 1975 the trial of nine young activists began. Known as the SASO Nine, or the Black Consciousness Trial, it was to be a milestone in the politics of the era, and beyond.

Thirteen members of SASO and other Black Consciousness-affiliated organisations were arrested on charges of treason. This was after they defied a police ban and held rallies at Turfloop and in Durban to celebrate the independence of Mozambique, which was achieved in September 1974.

Of the 13 students and young activists, the state charged nine with treason, initiating what became the longest political trial in South Africa at the time.

The trial

South Africa’s longest terrorism trial played out over the course of 17 months and garnered substantial press coverage.

The nine young men charged in the trial came to play a pivotal role in the broader public conception of SASO. They were also to have a catalytic politicising affect across the country. And their names live on as veterans of the fight against apartheid. They were Zithulele Cindi, Saths Cooper, Mosioua Lekota, Aubrey Mokoape, Strini Moodley, Muntu Myeza, Pandelani Nefolovhodwe, Nkwenke Nkomo and Gilbert Sedibe.

Legal historian Michael Lobban argued in his book, White Man’s Justice: South African Political Trials in the Black Consciousness Era, that the trial offered particular insights into how the South African state sought to,

use a political trial to control its opponents.

In Limpopo’s Legacy I argue that the trial also demonstrates the way that young activists used the court system and attendant press coverage to propagate their own political agenda. This was especially important for defendants who were students from Turfloop, who were under a gag-order on campus, and for those who were banned from publishing or public speech.

These defendants came to be the public face of student resistance at the outset of their trial in 1975. It provided a platform to highlight their cause.

The court room as theatre

Historian Daniel Magaziner has said in the book The Law and the Prophets that,

the trial was more farce than tragedy, and, reasoning that some sort of conviction was inevitable, the defendants treated it like theatre.

While theatricality did play a role in how the defendants presented themselves on the stand, there were serious motives behind this performance.

More than a stage, the defendants used the stand as a microphone, and indeed a pulpit from which to propagate their message. Famously, Steve Biko, SASO’s founder and figurehead, took his opportunity on the witness stand to expound on the philosophy of Black Consciousness as the guiding principle for SASO and the Black People’s Convention (BPC). The BPC was an affiliate of SASO that organised non-students around the ideals of Black Consciousness.

In his explanation to the presiding judge Biko stated:

Basically Black Consciousness refers itself to the black man and to his situation, and I think the Black man is subjected to two forces in this country. He is first of all oppressed by an external world through institutionalised machinery: through laws that restrict him from doing certain things, through heavy work conditions, through poor education, these are all external to him, and secondly, and this we regard as the most important, the black man in himself has developed a certain state of alienation, he rejects himself, precisely because he attaches the meaning white to all that is good, in other words he associates good and he equates good with white. This arises out of his living and it arises out of his development from childhood… This is carried through to adulthood when the black man has got to live and work.

Redressing this psychological conditioning formed the core thrust of the Black Consciousness movement.

Over the course of five days of testimony in May 1976 Biko ranged from discussing the psychological grounding of the SASO slogan “Black is beautiful” to the importance of disinvestment in South Africa by foreign firms.

Fifty years after the founding of SASO – and nearly 45 years since the historic trial of the SASO Nine – the tactics, strategy, and ideas of this anti-apartheid student movement remain a model for student activists.![]()

Anne Heffernan, Assistant Professor in the history of Southern Africa, Durham University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Written by: Natasha

Similar posts

MORE ARTICLES

In Pictures: Mzansi Celebs serve style and drama at Durban July 2025

Five killed in KZN crash allegedly caused by Polo driver

From Benin to the world: Kidjo makes history as first black African on Hollywood Walk of Fame

Drama, cheating and Surprise guest: RHOD reunion delivers shocking revelations

Why Waterfall Estate’s 99-year lease is practically forever

QUICK LINKS

UpComing Shows

Touch of Soul

With T Bose

Kaya 959 takes back Sundays with A Touch of Soul, the only show bringing you soul and RnB music that touches your mind, body and spirit. The Best T in the City, T-bose takes you back to a time when music was made to last. A Touch of Soul is the perfect wind-down to your weekend. Sundays 14h00 to 18h00.

close

The Jazz Standard

with Brenda Sisane

The Jazz Standard with Brenda Sisane. Sunday's 12:00-15:00.

close

Spade of Hearts

With Xola Dlwati

WITH XOLA DLWATI: SATURDAYS 12:00 -15:00 Spade of Hearts is a fuse of love and soulful sounds, pulling at your heartstrings. Tune in for songs that will take you down memory lane. It is the sound that once dominated your playlist. It airs Sundays 12:00 – 15:00.

close

The World Show

With Nicky B

The World Show is informative, expansive, and largely pan-African. This is a musical journey that bridges generations and genres, travelling across continents and timelines, with in-depth interviews and features. ‘The World Show’ is a four-hour global journey through sound – featuring the freshest tracks from home and afar.

close

959 Music Weekdays

Kaya 959 Hits

Real. Familiar. Memorable. Kaya 959 brings you the music you know and love from our playlist. Uninterrupted. Thursdays 20h00 to 21h00

closeConnect with Kaya 959

DownLoad Our Mobile App

© 2025 Kaya 959 | On The Street On The Air