Everyday homophobia and imposed heterosexuality in football

By: Sylvain Ferez, Université de Montpellier

Canaries.co.uk

How many top athletes worldwide are openly gay? And how were their coming outs received? In 2018, the issue of homosexuality in sport is still taboo and creates discomfort among both players and fans.

Recent surveys indicate that in a number of countries, the public is more accepting of gay athletes. A 2018 poll in France found that 85% of those surveyed felt that homosexuality in football was “acceptable” and that it was important to fight homophobia. A US poll, conducted in 2014 after NFL draft prospect Michael Sam announced that he was homosexual, found that 65% of Americans would be supportive of a gay athlete on their team, with 46% strongly supportive.

But that’s not the case worldwide. The 2018 World Cup is being held in Russia, a country that is seen as particularly homophobic. Among other legislative actions, in 2013 Russia banned “gay propoganda”, and during the ongoing competition homophobic chants have been widespread.

While football is a discipline that presents itself as neutral, universal and in a way, desexualised, it is important to examine the sport’s deep heterosexist foundations.

Coming outs are rare

In a 2009 autobiographical work, I’m the Only Gay Football Player, or I Was…, amateur-league French footballer Yohan Lemaire wrote about the unexpected cost that his coming out to his teammates had. This year he completed a documentary, Footballer and Gay: One Doesn’t Rule Out the Other, which was broadcast on the France 2 television channel.

The process Lemaire describes is similar to that found in North American contexts, with three stages. Initially there’s the fear of speaking out, followed by efforts to control all signs that might betray one’s sexuality – even to the extent of producing the appearance of heterosexuality to avoid questions – in an environment perceived as extremely hostile. Finally, after the announcement the strongest impression is generally surprise at not being excluded. The much-feared storm fails to erupt. But heterosexist culture persists, meaning that many players eventually withdraw of their own volition, no longer able to tolerate it.

Paying the price of intolerance

Is this why so few players come out? And why those who do sometimes pay a high price?

In May 1998, during that year’s World Cup competition, Justin Fashanu, once seen as one of English football’s great hopes, committed suicide. He came out eight years earlier, but his doing so had the opposite of the intended effect. He quickly became a scapegoat for fans and fellow professionals, and at Nottingham Forest, his own trainer echoed supporters’ insults, calling Fashanu “a fairy”. He was obliged to switch clubs several times.

After France won the World Cup that year, the French LGBT magazine Têtu highlighted the invisibility of homosexuality in professional football. As there were questions about the sexuality of France’s goalkeeper, Fabian Barthez, Têtu wondered if there might not be “one or two real gems” among France’s team.

History of modern sport

During the second half of the 19th century, sport became an independent practice, separated from other social activities. The normalisation of heterosexuality is an inherent part of that history. Engaging in sports implies the desexualisation of the human body, the neutralisation of its erotic power. Contact with other bodies is functional, and sexuality is set aside.

Collective manifestations of joy in football – after a goal is scored or a match won – are no exception to this. They are ritualised expressions that, from the perspective of those performing them, are in no way sensual.

Indeed, if football provides insight into sexuality, it is only in a roundabout way, through the performance of a cold, pragmatic virility. This virility is based on two implicit assumptions: there is no sexuality in the game, and there is no place for homosexuals.

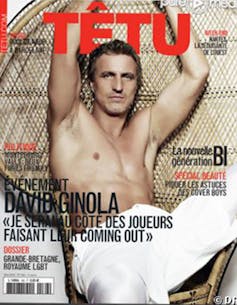

This is also why, early on, the magazine Têtu took the opposing view of traditional football culture, hypersexualising elite footballers and trying to identify gay players in their ranks. In June 1996, French football player Eric Cantona was presented as part of a “new gay generation”, and in 2011 the magazine gave a cover treatment to former player David Ginola, outspoken for his support of gay players and efforts against homophobia.

A footballer’s body is always heterosexual

Têtu/Pure Medias

Such coverage aside, the body of a footballer remains under strict heterosexual embargo. In June 2018, US soccer player Collin Martin came out as gay, the first to do so since England’s Robbie Rogers in 2013. In France, Olivier Royer is the only professional footballer to have publicly revealed his homosexuality. But he did so in 2008 at the age of 52, long after the end of his career.

There is substantial official support for more tolerance in football, including the 2004 commitment by the top French club, Paris Saint-Germain (PSG), to fight homophobia. In September 2007, PSG drew up a charter against homophobia in the sport, and nine Premier League and League 2 clubs joined the effort. In England, dozens of football teams have taken part in the Stonewall Charity’s “Rainbow Laces” campaign, which combats discrimination against LGBT fans and players.

In France there was even a gay football club, Paris Foot Gay (PFG), created to raise public awareness of homophobia. However, in 2015 the organisation published a terse press release that announced the dissolution of PFG:

“In the face of remarkable indifference, reluctance on the part of institutions to actually commit, and the shame some still associate with this topic, we must face facts: we can no longer make progress in our fight against homophobia.”

Culture of homophobia

While there has been a great deal of talk and a large number of initiatives aimed against homophobia in football, real change remains elusive. This is because homophobia is perpetuated through everyday behaviour in less official channels.

For example, in 2009, Louis Nicollin, president of the Montpellier Hérault Sport Club, called Auxerre player Benoît Pedretti a “little faggot” in a TV interview. Nicollin, known for his “slip-ups”, was sanctioned and eventually apologised. Another example took place in Australia in 2014, when TV commentator Brian Taylor called AFL player Harry Taylor a “big poofter” during a broadcast. Brian Taylor’s comments were widely criticised and he too apologised.

Yet such corrosive insults are far from absent on the field. Slurs like “faggot” and “cocksucker” are repeated ad infinitum. In the 2018 World Cup, Argentina’s team was heavily fined after its fans sang homophobic songs, as was Mexico’s team. When the offending players or fans are called to order, they often claim that their insults had nothing to do with sexuality – they are simply adhering to the collective definition of what is considered negative. The sexuality of the person targeted by the insult is not truly at issue. Culturally, their heterosexuality is assumed, like that of all the other players.

Without seeming so, such slurs are a way of defining what a football player must be. A way of evoking not only the values shared within the world of football but also the sexual orientation that is supposed to embody them. That is why football leaves little or no room for narratives outside of the established “norm”.

![]() Translated from the French by Alice Heathwood for Fast for Word and Leighton Kille.

Translated from the French by Alice Heathwood for Fast for Word and Leighton Kille.

Sylvain Ferez, Maître de conférence, sociologie, Université de Montpellier

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Written by: Natasha

Similar posts

MORE ARTICLES

Two boys accused of killing Grade 10 pupil remain behind bars

45 individuals arrested in Pretoria for drunk driving over the weekend

Pics: Inside Liesl Laurie-Mthombeni’s girls’ vacation

Berita celebrates 34th birthday with new single ‘Gugulethu’

Gauteng settles major e-toll debt with R5.4 billion payment

QUICK LINKS

UpComing Shows

959 Music Weekdays

Kaya 959 Hits

Real. Familiar. Memorable. Kaya 959 brings you the music you know and love from our playlist. Uninterrupted. Thursdays 20h00 to 21h00

close

The Best T in the City

With T Bose

He has held it down in the world of mid-morning radio with the best music, riveting topics, brilliant mixes and interesting guests. Every weekday, The Best T proves why he is the BEST by connecting to you like only your bro or favourite uncle could. He lets his listeners dictate the songs they want to hear in the ever-popular Top 10 at 10, and his Three Teaspoons never run out. Catch The Best T in the City Mondays to Fridays from 09h00 to 12h00.

close

Feel Good

With Andy Maqondwana

Feel good about feeling good! That's exactly what The Feel-Good show is about. An escape from the negativity that surrounds us, indulging you in good feels. Pass it on to one and all. Spread the good feeling around Gauteng with Andy Maqondwana.

close

Kaya Biz

With Gugulethu Mfuphi

The world of business is simplified for you by Kaya Biz with Gugulethu Mfuphi. This fast-paced award-winning business show talks to the corporate giants as well as up and coming entrepreneurs about their wins and challenges. Gugulethu invites guests to offer their analyses of markets and economies, and also delves into issues of personal financial wellness. Kaya Biz airs Mondays to Thursdays 18h00 to 19h00.

close

Point of View

With Phemelo Motene

Point of View with Phemelo Motene delves into the day’s current affairs, touches on real issues that affect people’s daily lives and shares expert advice on questions posed by the audience. Mondays to Thursdays 20:00 to 22:00.

closeConnect with Kaya 959

DownLoad Our Mobile App

© 2025 Kaya 959 | On The Street On The Air