Why new South African law won’t end the toxic mix of money and politics

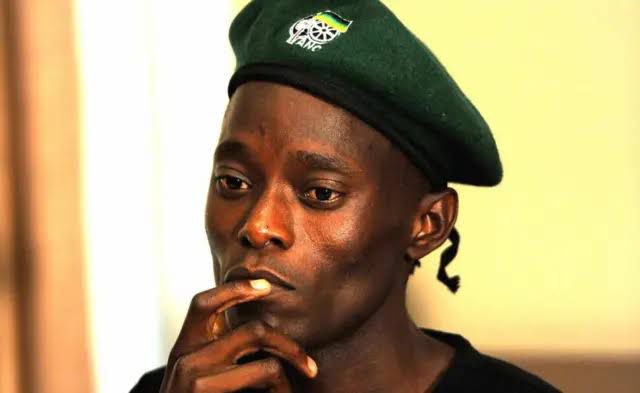

EPA-EFE/Yeshiel Panchia

Steven Friedman, University of Johannesburg

The grip of money on South African politics may be so tight that it could be impossible to govern – or seek to govern – unless you are beholden to private money.

Can a new law change that?

The Political Party Funding Act was signed into law by President Cyril Ramaphosa early this year. It forces parties to disclose donations of R100 000 (US$6700) or more and sets up a Multi-Party Democracy Fund to which donors who want to support a range of parties can donate.

The Independent Electoral Commission, which will implement the law, decided that it would not come into force until regulations on how it will operate are drafted. It has now concluded hearing evidence from “interested parties” – mainly political parties and non-governmental organisations – on how to word the rules.

Democracy campaigners have been pressing for this law for years. Until it was signed, South Africa had no laws governing donations to parties: the wealthy could give huge amounts to parties and were not obliged to reveal this.

Toxic relationship

In any democracy, such secrecy should trigger fears that government decisions will reflect not what voters want but what large donors require. In South Africa, the fear is particularly justified because the relationship between money and politics is close and toxic.

This is a product of the past and the transition to a new political order. Apartheid ensured that whites owned the large companies and so most of the wealth. When black parties were allowed to operate freely from 1990, their only source of significant money (apart from aid donors and government funding from 1994) was business.

This created huge openings for companies or their owners to buy cooperation. The new law is meant to control this by forcing large donors to make their donations public.

Read more:

Economic exclusion feeds the politics of patronage in South Africa

The democracy fund may be partly inspired by corporations which donate openly to several parties as a social investment project. Public funding is allocated mainly in proportion to parties’ support at the last election, which favours big parties: the corporates use criteria which advantage smaller parties in the hope that this will “level the playing field”. The fund is meant to offer a larger vehicle for this democracy support.

Campaigners have welcomed the law as a step forward but are concerned that loopholes may make it possible to continue to buy party support: R100 000 is a generous ceiling. Ways are also needed to stop big donors giving multiple donations of just under R100 000 to circumvent the law; the Independent Electoral Commission was asked at the hearings to draft regulations to curb this.

They are right to be concerned about the limits of the law – but equally right to expect that, when it is enforced, voters will know more about who is funding parties, even though South Africa’s law offers less control than similar laws in some other democracies. But this may make little difference to the really toxic influence buying: the greatest threat to democracy is the money which buys politicians, not parties. And the law does not regulate this.

Buying influence

South Africa is trying to emerge from a decade in which private interests made deals with politicians and officials to make government work for them alone. The hearings of the commission of inquiry into “state capture”, chaired by deputy chief justice Raymond Zondo, regale the country with evidence of abuse of public money and trust.

But party funding has been a minor player at the hearings – private interests mostly gained control of government by buying people, not parties. The much-reviled Gupta family, former President Jacob Zuma’s friends accused of having captured his administration for their own ends, did donate to parties. These included the official opposition, the DA. But, it allegedly gave far more to individuals.

Internal party elections are at least as much a problem as the national contest – black-owned companies in particular are repeatedly approached to fund contests for party office.

The problem has been emphasised by “leaked” emails from within Ramaphosa’s ANC Presidency campaign, which are currently receiving media coverage. Ramaphosa’s opponents say they show he misled Parliament when he told it he was unaware of a donation from a company named at the commission. Whether or not this is true, the emails show an attempt to raise very large sums from private donors whose identity was not revealed because the law does not require this.

Murky links

These links between politicians and money are another product of past inequities. In the early 1990s, anti-apartheid activists emerged as a government in waiting. But they had no money and could not afford the lifestyle which matched their future role. Businesses and business people – some to help, some because they wanted influence – provided them with houses, cars and other passports to the middle class.

At the same time, white-owned businesses recognised that they needed black partners; the only candidates they knew were the political activists who exhorted them to end racism – and so activism became a route to company boards.

The pattern this created survives today. Links between politicians and private money are murky and raise perpetual doubts about whether political decisions respond to voters or patrons.

So pervasive is this mix of private wealth and public office that it is open to question whether it is possible to achieve a senior position in government without being beholden to private donors. Ramaphosa is a wealthy man and so are some of his political allies. If they cannot run a campaign which does not rely on wads of money from people who are never voluntarily named, why believe that anyone else can?

If Ramaphosa’s campaign funding were to cost him his presidency, he would no doubt be replaced by someone else who received large donations about which voters know nothing. This would apply even if the replacement led an opposition party.

The two next biggest parties are the DA, which is sceptical of the Party Funding Act because it says its donors want anonymity to avoid reprisals. The other is the Economic Freedom Fighters, one of whose key funders owns a cigarette company which has been accused of improper influence on the tax authorities.

So, South African voters are likely to find that whoever governs them relies on donors whose names they do not know.

Uphill battle

The link to money will continue to damage South African politics unless the flow of undisclosed money to politicians ends. This depends far more on what parties do than on law. The ANC has told the Independent Electoral Commission it is determined to find ways of fixing its problem, but it faces an uphill battle. Other parties, including the DA and Inkatha Freedom Party, which are in government in provinces and municipalities, have yet to acknowledge that they have a problem.

Given all this, South Africans will not know soon who pays for the politicians who are meant to serve them.![]()

Steven Friedman, Professor of Political Studies, University of Johannesburg

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Written by: Zuko

Similar posts

MORE ARTICLES

SA will be charged a tariff of 30% by the US starting on August 1st

WATCH: Minnie celebrates her wins, lessons and blessings on her 35th birthday

ANC Youth League demands justice for Sindiso Magaqa beyond hitman’s conviction

Liverpool FC vows to pay out Diogo Jota’s R350 million contract to his widow

The World Show with Nicky B broadcasts live from France

QUICK LINKS

UpComing Shows

The Best T in the City

With T Bose

He has held it down in the world of mid-morning radio with the best music, riveting topics, brilliant mixes and interesting guests. Every weekday, The Best T proves why he is the BEST by connecting to you like only your bro or favourite uncle could. He lets his listeners dictate the songs they want to hear in the ever-popular Top 10 at 10, and his Three Teaspoons never run out. Catch The Best T in the City Mondays to Fridays from 09h00 to 12h00.

close

Feel Good

With Andy Maqondwana

Feel good about feeling good! That's exactly what The Feel-Good show is about. An escape from the negativity that surrounds us, indulging you in good feels. Pass it on to one and all. Spread the good feeling around Gauteng with Andy Maqondwana.

close

Kaya Biz

With Gugulethu Mfuphi

The world of business is simplified for you by Kaya Biz with Gugulethu Mfuphi. This fast-paced award-winning business show talks to the corporate giants as well as up and coming entrepreneurs about their wins and challenges. Gugulethu invites guests to offer their analyses of markets and economies, and also delves into issues of personal financial wellness. Kaya Biz airs Mondays to Thursdays 18h00 to 19h00.

close

Point of View

With Phemelo Motene

Point of View with Phemelo Motene delves into the day’s current affairs, touches on real issues that affect people’s daily lives and shares expert advice on questions posed by the audience. Mondays to Thursdays 20:00 to 22:00.

closeConnect with Kaya 959

DownLoad Our Mobile App

© 2025 Kaya 959 | On The Street On The Air